When I finished high school, Dad asked me about my plans.

I said, “I want to be a veterinarian.”

He said, “Why not be a real doctor?”

I said, “OK.” I went to college and medical school.

After my internship, I volunteered for the Army medical corps. I served in the South Pacific as a general medical officer with the 102nd Station Hospital, as a dermatologist with the 35th General hospital, and as an anesthetist with the 58th Evac Hospital. When I returned home, I knew I wanted more medical training. The experience as an anesthetist had been so interesting that I applied for a residency in anesthesiology at Charity Hospital in New Orleans, whose chief, John Adriani, mentored the best residency program in the States. It was his books on the chemistry and physiology of anesthesia that I referred to while learning on-the-job as an anesthetist in surgery at the 58th Evac.

I liked Dr. Adriani immediately. We met in the doctors’ dressing room of the surgical suite; he was in scrubs and we sat on benches and chatted. He was in no hurry to end my interview and proceeded to tell me why he had given up his surgical training to become an anesthesiologist: after he had finished his residency in general surgery, he didn’t feel capable of doing more than appendectomies and repairs of hernias. He knew he was better than that which led him to learn about anesthetics and become the medical profession’s leader in that specialty. I left him, excited and ready to learn from him.

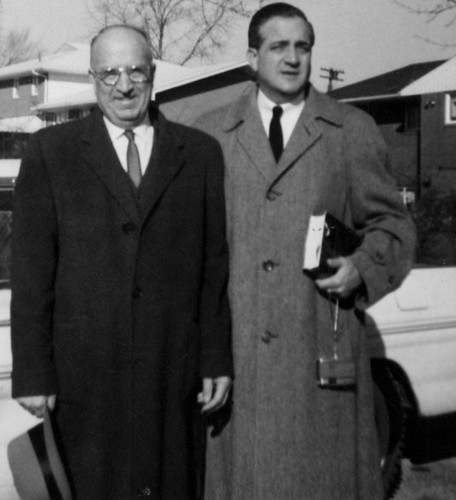

When Dad asked me what I was going to do now that I was home from the army, I said I was going to be an anesthesiologist. He said, “You ought to be a heart doctor and take care of people.” I said I would. I canceled the residency in anesthesiology, took residencies in chest and internal medicine, and eventually became an internist.

Now, some fifteen years after I’ve retired from the practice of medicine, I’ve been thinking: What would my life have been as a veterinarian? What would my life have been if I had become an anesthesiologist?

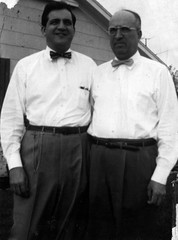

Those are interesting questions. That I still remember the episode after 65 years emphasizes the impact of Dad’s influence on my life. It also points out my failure to have a strong feeling about my right to make my own decisions. I was able to accept the change in my goal; I became an internist with a strong interest in diseases of the lung. I cared for my patients and took good care of them. I was a good role model for my sons; all three became healers, (two physicians and a psychotherapist) and excellent ones, too. I made a “good” living for our family.

How would Dad have reacted if I ignored his wish that I become a “heart doctor” and train to be a vet or an anesthesiologist? He would have been disappointed, I know, but he would have accepted my decision and remained interested and supportive. This recalls my decision to join a reform congregation rather than a conservative or orthodox one that I knew Dad expected when we moved to Houston. To better understand my choice, Dad spoke with Robert Kahn, our rabbi at Temple Emanu El, at a Friday evening service. I don’t know what was said during their brief chat, but whatever it was, it lifted the load from Dad’s heart about my choice. The matter never came up again. Similarly, if I had chosen veterinarian medicine or anesthesiology, I believe Dad would have had a talk with my mentor to gain some insight into my work and, so, would have been more at ease about my future and even actively supported me.

As a vet or as a “passer of gas” as anesthesiologists are accused of being, would I have seen myself as having diminished stature in the medical or professional community? Would I feel I were a slacker, one having less ambition if I were to choose a profession that required less training, less expense, less study, less training than a “heart doctor?” That would be a side issue that I know I would have to confront; it would part of my agenda to be the best of my choice, to explore all new ideas, all frontiers so that I would stand out in my own mind. No matter my choice, I knew Yvette would support me and defend me and make my professional and home life the best for both of us.

If I had chosen to be a vet or an anesthetist, what kind of doctor would I have been? I am drawn to animals and I’m certain I would have loved taking care of them. Loving my patients and wanting them to be well would have been a combination of attitudes that would have made me happy in my work. As to being an anesthetist, I remember, to this day, how much I wanted to be mentored by Adriani. He was thoroughly at ease, had no airs about him, like a good father, a father figure who would never be a tyrant, who would want his house staff to be the best because they respected him, wanted to learn, and wanted to please him. So, I knew that either choice of medicine I had in mind to pursue was really going to be right for me.

I did become an internist though not the cardiologist that Dad aspired for me. With time my practice evolved into seeking out my patients’ inner needs as well as their physical needs. My combination of interest in both physical and emotional matters was deeply satisfying for me; I was successful in learning to take care of the “whole” patient, the goal of a true physician.